PSAT Reading Practice Test 10

Questions 1-9 refer to the following information.

This passage is adapted from E. Gene Towne and Joseph M. Craine, "Ecological Consequences of Shifting the Timing of Burning Tallgrass Prairie."© 2014 by E. Gene Towne and Joseph M. Craine. A forb is an herbaceous flowering plant.

Periodic burning is required for the maintenance

of tallgrass prairie. The responses of prairie vegetation

to fire, however, can vary widely depending upon

when the fires occur. Management and conservation

05objectives such as biomass production, livestock

performance, wildlife habitat, and control of specific

plant species, often influence when grasslands are

burned. In some prairie regions, timing of seasonal

burns have been used to manipulate the balance of C3

10and C4 species, control woody species, stimulate grass

flowering, and alter the proportion of plant functional

groups. Most grassland fire research, however, has

focused on either burn frequency or comparing

growing season burns with dormant season burns,

15and there are few studies that differentiate effects

from seasonal burning within the dormant season.

In the Kansas Flint Hills, when prairies are burned is

an important management issue, but the ecological

consequences of burning at different times are poorly

20understood.

The Flint Hills are one of the last remaining

regions supporting extensive native tallgrass prairie

in North America and frequent burning is integral

to its preservation and economic utilization. Since

25the early 1970's, recommendations have been to burn

Kansas Flint Hills grasslands annually in late spring,

typically once the dominant grasses have emerged

1.25–5 cm above the soil surface. Although frequent

late-spring burning has maintained the Flint Hills

30grassland, the resultant smoke plumes from en masse

burning often leads to air quality issues in nearby

cities. Concentrated smoke from grass fires produces

airborne particulates, volatile organic compounds,

and nitrogen oxides that facilitate tropospheric ozone

35production. Burning in late spring also generates more

ozone than burning in winter or early spring due to the

higher air temperatures and insolation.

If the Flint Hills tallgrass prairie, its economic

utilization, and high air quality are all to be

40maintained, a good understanding of the consequences

of burning at different times of the year is necessary.

Burning earlier in spring has been regarded as

undesirable because it putatively reduces total biomass

production, increases cool-season [grasses] and

45undesirable forbs, is ineffective in controlling woody

species, and lowers monthly weight gains of steers

compared to burning in late spring. Consequently,

burning exclusively in late spring has become

ingrained in the cultural practices of grassland

50management in the Flint Hills, and local ranchers often

burn in unison when weather conditions are favorable.

Despite long-standing recommendations that

tallgrass prairie be burned only in late spring, the data

supporting this policy is equivocal. Total biomass

55production was lower in plots burned in early spring

than plots burned in late spring, but the weights

included grasses, forbs, and shrubs. It was not known

if [grass] biomass was reduced by early-spring burning

or if the differences were a site effect rather than a

60treatment effect. Burning in early spring also shifted

community composition in a perceived negative

pattern because it favored cool-season grasses and

forbs. This shift in community composition, however,

may actually be desirable because many cool-season

65grasses have higher production and nutritional quality

than warm-season grasses at certain times of the year,

and many forb species are beneficial to the diet of

grazers. Burning in late spring has been considered

the most effective time to control invasive shrubs,

70but Symphoricarpos orbiculatus was the only woody

species that declined with repeated late spring burning.

Finally, average weight gain of steers was lower in an

unburned pasture than in burned pastures, but there

was no significant difference in monthly weight gain

75among cattle grazing in early-, mid-, or late-spring

burned pastures.

The historical studies that formed the foundation

for time of burning recommendations in tallgrass

prairie are inconclusive because none had

80experimental replications and most were spatially

limited to small plots. All of these studies were

interpreted as suggesting that shifting the time

of burning by only a few weeks would negatively

influence the plant community. A more recent large-

85scale replicated study that compared the effects of

annual burning in autumn, winter, and late spring

found that the timing of burning had no significant

effect on grass production and no reductions in the

composition of desirable warm-season grasses.

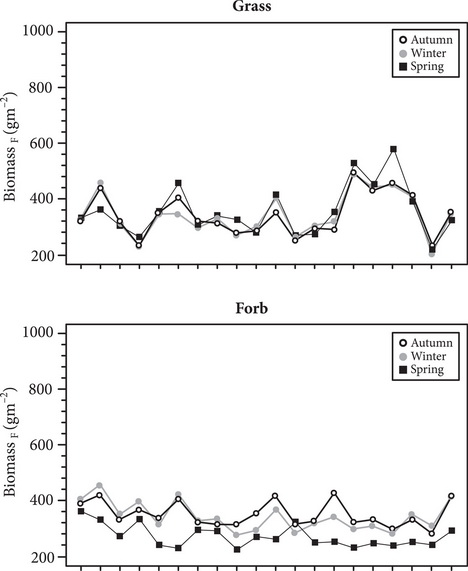

Changes in Upland and Lowland Grass (a) and Forb (b) Productivity Over Time for Autumn-, Winter-, and Spring-Burned Watersheds